Earlier this month, we filed suit against the City of Sonoma for unlawful denial of a proposal to construct three homes. We’re fighting for much more than just three homes, though.

California has been experiencing a crisis-level housing shortage for decades. In recent years the problem has finally reached the well off white middle class, bringing the housing question to popular consciousness. While there has been a true shortage of affordable housing for decades, the problem has mostly been borne by the poor, the working class, communities of color, and people who exist at the intersections of each. Of course, this is the United States, where a problem doesn’t rise to the level of urgency until middle class whites are affected. We chose this; we can choose something else, if we want to.

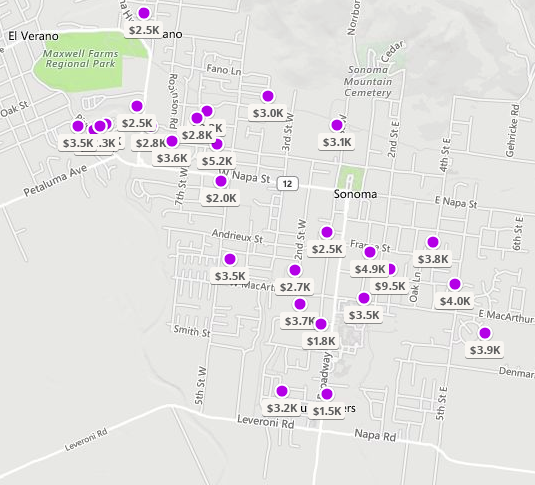

A quick unscientific look at Zillow.com indicates that average rents in Sonoma are upwards of $2,500 per month and reach as high as $5,000 per month for a 3 bedroom home. By comparison, East Oakland rents start at $1,500; nearly half as expensive.

A quick unscientific look at Zillow.com indicates that average rents in Sonoma are upwards of $2,500 per month and reach as high as $5,000 per month for a 3 bedroom home. By comparison, East Oakland rents start at $1,500; nearly half as expensive.

The California State Department of Housing and Community Development requires cities to issue an annual update on progress towards meeting regional housing allocations. Sonoma is currently required to produce 137 units of housing (affordable and otherwise) between 2015 and 2023. So far the city has produced 47 units of affordable housing, while Oakland has produced 480 out of its 4,134 affordable unit mandate.

Riddle me this: Why is Sonoma, a city with rents twice as high as deep east Oakland, producing barely any affordable housing while Oakland with its cheaper rents produces more? Why is the more expensive city required to produce less affordable housing than the cheaper one?

In any reasonable system of housing allocation, it would make intuitive sense to require the more expensive city to build more affordable housing. After all, if we are trying to make California affordable for everyone, it would make the most sense to spend scarce public dollars in the way that would make the biggest impact.

Both of the above questions can be answered, rather unsurprisingly, with an analysis of the outsized power white homeowners have over rental communities of color. These Regional Housing Needs Allocation numbers (RHNA) are allocated to each city using a political process. While new state law is being developed and implemented to instead favor reliance on hard data, a political process leads to the predictable outcome that those with the most power win in the end. This is why Sonoma is able to demand a lower allocation of affordable housing than Oakland, despite the former being wildly unaffordable compared to the latter.

This explains the mechanism behind the absurdly low RHNA requirements, but what is the mechanism behind the low numbers of production? The power dynamics are similar, however there is an important component of our current capitalist free market system of housing allocation that must be considered. While The State is not able to produce housing in the quantities we need (viz. Article 34 of the state constitution), we must rely on the private market to produce affordable housing.

Relying on the private market to produce housing means the housing we only ever see proposed is what the private market deems financially feasible. What we don’t see is the housing that isn’t proposed. Why aren’t we seeing affordable housing proposed in Sonoma while we’re seeing it proposed in Oakland despite completely opposite needs?

Again, the outsized power of wealthy white landowners.

The City of Oakland has a remarkably fast approval process for housing developments. It can sometimes take as little as 6 months to go from proposing an idea to securing a building permit. In Sonoma, securing permits can take upwards of 5 years. The vast difference can be explained by the predictability of the process. Much of Oakland development is by-right, unable to be challenged or appealed. Sonoma holds the opposite.

Our lawsuit in Sonoma cuts at the heart of this issue. When financing affordable housing in our capitalist mode of production, you are often held to tight deadlines and narrow margins. Miss any of your grant deadlines by even a single day because one of your permits is held up? You could be out the millions of dollars necessary to provide much needed affordable housing. Spend a bit too much of the budget endlessly redesigning the building to appease the aesthetic preferences of the securely housed? Your project could no longer be competitive enough to win financing. Waste too much time fighting spurious appeals from neighbors who feel their views are more important than someone’s future home? You could find construction costs have risen enough in the interim to render your fragile budget completely unworkable.

A wildly unpredictable process like Sonoma’s is anathema to all the needs of affordable housing.

We filed our lawsuit to put an end to Sonoma’s capricious approval pipeline. Creating a predictable process is necessary for affordable housing—as we build it today—to flourish in Sonoma. Our suit doesn’t ask anything out of the ordinary: it isn’t challenging the city’s zoning, it isn’t challenging any fee structure, and it isn’t challenging the outcome of any CEQA analysis. Our suit only asks the City of Sonoma to follow their own rules with predictability and regularity.

The three homes on Brazil St played by the rules. They met every objective requirement, they slogged through the process, and yet despite all this they were denied for specious reasons. However, this is about much more than just three homes. Simply put: we’re asking the City of Sonoma to provide a legal environment in which California builds housing equal to its needs.

If Sonoma says no, we’ll ask a judge to force them to say yes. Being YIMBYs, we are very good at getting cities to say Yes.